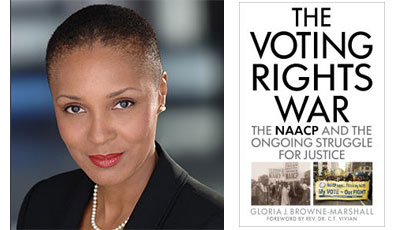

Three years ago, when Professor Gloria Browne-Marshall began writing her new book, The Voting Rights War: The NAACP and the Ongoing Struggle for Justice, she said it was with the idea that by the end of President Obama’s term, citizens might not be very enthusiastic about exercising their constitutional right to vote. Given the tumult of the current presidential election campaign, it seems she was on to something. “I wanted to remind people that the reason to vote is beyond any charisma for a particular candidate,” she said. “People paid with their lives in order for us to vote.”

Earning the right to vote for people of color in the United States has been a long and winding journey fraught with roadblocks, political oppression, institutional racism, and outright violence. Obstacles such as the grandfather clause, the literacy test, and all-white primaries have disenfranchised black voters for decades, but despite these setbacks, the story of acquiring the right to vote is one of power and triumph.

In the book, published Sept. 2 by Rowman & Littlefield, Browne-Marshall begins with the Springfield riots in Illinois, 1908, a moment when intense mob violence against blacks helped spark the formation of the NAACP, an organization that would take the lead in battling segregation and disenfranchisement across the United States. “But the issues around voting rights started 100 years before that,” she points out. “Literacy tests had lot to do with Irish Catholic immigrants, and some laws started off by disenfranchising other groups, like women.”

Following the abolition of slavery and the enfranchisement of black males in 1870, Browne-Marshall said, “U.S. senators, state representatives, lieutenant governors, many of these positions were held by blacks around the South. And little by little, segregationist laws were put into place. They enacted literacy test laws as well as the grandfather clause, and disenfranchisement by felony conviction, which still exists today.”

This speaks to another theme of The Voting Rights War – that the struggle to earn the right to vote is still not over for many minority groups in the United States. “Laws can look equal on the face but have a discriminatory impact when it comes to certain groups and people. You see this clearly with the photo I.D. law in Indiana today,” she said. Laws like these require a photo I.D. to cast a vote, and to get a photo I.D., one typically needs a birth certificate. “I think I left mine in my sock drawer, but if I had to get it, I’m not sure if it’s still there,” Browne-Marshall said.

In researching The Voting Rights War, Browne-Marshall paid several visits to the Library of Congress, where she was able to read letters from the early 1900s, written by African Americans to the NAACP seeking legal advice. Many came from poor, rural blacks living in the Deep South, areas where voter suppression was at its peak. “It was amazing to read these original, handwritten letters depicting the danger they were in, and still asking for help,” the professor said. “No sheriffs or lower courts would help them, but they were still standing up against this regime asking for help.”

One such man, Vernon Dahmer, wrote on his tombstone, “If you don’t vote, you don’t count,” a view that Browne-Marshall endorses. “At the very end, people died for these rights,” she said. “People think they shouldn’t vote because it doesn’t count. But we should exercise it. It’s not perfect but it’s all we’ve got.”