“Get big money out of politics.” It’s a refrain heard time and again during election season, and the 2016 Presidential campaign is no different. The corrupting influence of money on politics seems to be the only issue that Republicans and Democrats can agree on these days, with each candidate promising not to let donations dictate their decisions.

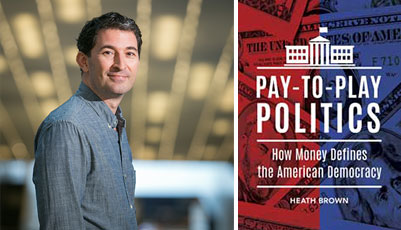

But it’s not quite that simple, insists Assistant Professor Heath Brown of the Department of Public Management. Brown’s latest book, Pay-to-Play Politics: How Money Defines the American Democracy, which will be published April 28 by Praeger, attempts to reconcile the disparity between an American public that simultaneously rejects the role of money in politics, yet regularly re-elects the wealthiest of candidates.

“There’s a whole lot more money being passed around now than in 1976,” Brown noted, “and in my book, I want to ask: what’s the impact of that? Has it been harmful to democracy, or is it simply a part of democracy?”

Brown focuses on 1976 for good reason. That was the year the U.S. Supreme Court decided the landmark case of Buckley v. Valeo, in which the Justices struck down limits on campaign spending for candidates, but upheldlimits on how much money an individual citizen could donate to a campaign. It was the case in which the right to donate and/or spend money on the campaign trail became directly associated with the First Amendment, a debate that carries on today, and is closely linked to the Citizens United case of 2010 in which the Supreme Court held that campaign donations were a form of free speech, and in turn opened the flood gates to virtually unlimited corporate spending on political campaigns.

Brown does not set out to answer whether or not money should be viewed as free speech. Instead, he asks another, more nuanced question: Does money actually buy votes, or does it influence politics in more subtle ways that have yet to be realized?

“People often think that money will affect the final vote, but we don’t have much evidence of this. What we do see,” he explained, “is that money can shape the political agenda. Congress only has so many days in the year, and they can’t spend a lot of time on every single issue. So money can influence Congress to focus on certain topics at the expense of others.”

Brown also emphasized that money influences the number of times someone can fight for an issue. Most people fighting for a change in policy are unsuccessful on the first attempt – but with enough funding, they can fight their battle on every possible front, and greatly increase their chances of winning.

“Another thing that’s changed since the 70’s is transparency,” said Brown. “There used to be very little accounting of campaign contributions and expenditures. But today, any random citizen can go online and know exactly how much Hillary Clinton has raised from a certain individual, or whether a certain industry is backing Ted Cruz. That has resulted in a much greater awareness of the role that money plays.”

Overall, Brown emphasizes that the role of money in politics should not be ignored, but rather that the public should look at the right issues. “Evidence suggests that voting is not clearly tied to campaign contributions, and that the candidate who raises the most does not always win,” he said.

Brown also leaves the reader with something unexpected – a reason to appreciate the role of money in politics. “Money has the possibility of bringing new voices into the political process, and allowing people outside of the two parties to run for office,” he observed. “If you can independently raise money, you can essentially buck the system.” Brown pointed to New York City’s matching funds program as an example, in which for every dollar a candidate raises, the city will donate $6 to the campaign. “It allows someone different to have access to politics,” he said. “It gives people a chance.”